Enjoying the spring-time garden of a house in the suburbs from the comfort of an armchair is not quite the same as hanging from a narrow tiny balcony of a city centre flat to catch a glimpse of the neighbourhood. Being an employee with a guaranteed salary and employment benefits, whose only concern is which teleworking platform to use, is not quite the same as being a low-wage cashier at a supermarket working without protective gear. Virtual class for a pupil in an urban centre with a broadband connection is not quite the same as that for a pupil on a mountain or island, with a slow internet connection and a prepaid card phone. Being Greek is not quite the same as being a refugee in a camp. Being a man is not quite the same as being a woman.

From the very first days of the quarantine, two different worlds started to emerge. The first world obsessed with making lists; lists of films, theatre performances, books and seminars available online. Aspiring creators perused all chronicles of epidemics. A story about Shakespeare, writing King Lear during the 1600 plague in England, became very popular in the social media. The second world too became obsessed with making lists. But these lists are more like survival charts: usually posted on the fridge door in the kitchen, in 24 lines – as many as the hours in the day – they strive to fit in a salaried teleworking job, virtual classes, cooking, washing, cleaning, grocery shopping and a bit of sleep. The first world was suffering from boredom. The other one from overworking. I wondered for days what the element that separated these two worlds was. That element was care. Those who had children, older and sick people in the house would have to leave their King Lear for later.

Quarantine at home: a woman’s affair

I had always been the one to take up more chores around the house and my free time was always less, compared to my husband. Now however, without even realising it, I have become the woman that my mother and granny used to be. I stepped into the role, sort of automatically, without any discussion. I was working in-between house chores and taking care of the children and my husband only went out for shopping. In just ten days, we had turned into a ‘60s couple.

Up to now, if both in a couple had to work, they would either have to pay for babysitter for the kids or hire a housekeeper or some other type of carer if there was a sick or older person in the house. At best, if granny and grandpa were available, they would lend them a hand. The quarantine came to change a decades-long unspoken agreement between couples in the developed world. No help was now available. Couples were on their own. Talking with families with children, I realised that the decision about who will assume this extra, unpaid care work in a household was no simple task. A small handful of couples managed to share their time in the day between work and children. Yet, in most cases, it was the woman who took on most of the care. Maria M. works in the media. On the very first day of the quarantine, she assembled a desk she found in the storeroom, for the room of her 10-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter. Although her employment contract was suspended a few days later and she received the 800 Euro special-purpose benefit, she continued to work with increased intensity to cover the hectic inflow of news. The same also applied for her husband. As an employee in the commercial department of a multinational consumer goods company, also on a suspended employment contract, he continued to work at a hectic pace, processing financial rescue plans for the company. The legal provision for a special-purpose leave to one of the parents could not be used. Maria’s parents, who were helping up to that time with grocery shopping, cooking and raising the children, and the housekeeper who cleaned the house once a week, were longer able to come. “I had always been the one to take up more chores around the house and my free time was always less, compared to my husband. Now however, without even realising it, I have become the woman that my mother and granny used to be. I stepped into the role, sort of automatically, without any discussion. I was working in-between house chores and taking care of the children and my husband only went out for shopping. In just ten days, we had turned into a ‘60s couple”.

Things seem to be even harder for single-parent households, most of which are mothers. Samantha K. is an English language teacher, living with her two sons, 5 and 12 years old. As we talk on Skype, I often see her children moving in the background – a scene that’s become familiar for all of us working from home. “As soon as the schools were closed, I had no time to even think what this quarantine is about; I had to organise a survival schedule under the new conditions. I created a framework for my online courses, I spread out my teaching hours across the seven days of the week, I discussed with the children which hours we would spend together and posted the schedule on the fridge. On top of that, I also had to care for my 80-year-old mother. No longer my helper in caring for my children, she became a person I had to ensure remained isolated in the house. I can’t keep up with the schedule on the fridge, but it is our goal and what keeps us alert”. Her income dropped by 30%, but she no longer has to pay for a babysitter and for private tutoring for her older son, so – for the time being – stressing out about survival can wait.

Women on the front-line

During the pandemic, people in many countries around the world stood in their balconies to applaud the “heroes” of the crisis. As they were clapping perhaps they didn’t know that this applaud was mainly honouring women. On a global scale, according to a World Health Organisation report, 70% of healthcare employees, especially nurses, midwives and social workers, as well as people working in cleaning, laundries and catering are female.

Fear dominates. A colleague’s partner asked her to sleep at the hospital, while in another case a couple rented a second house to ensure that the virus was not transferred to their home.

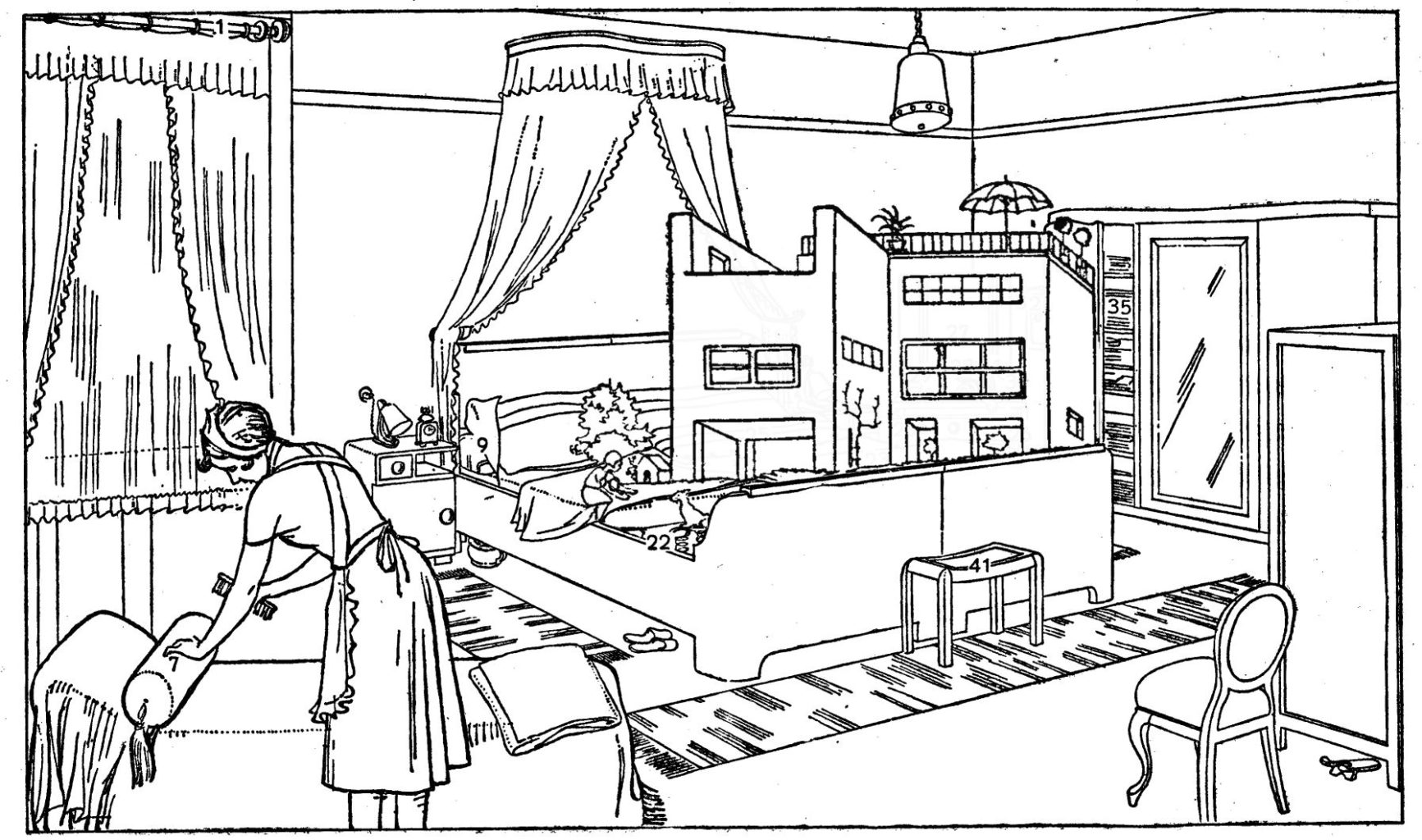

Statistics from Italy and Spain show that infected healthcare professionals are overwhelmingly more women than men. The nurses I’m in touch with describe a situation they know far too well. Fights against invisible enemies they have fought before. Strict safety measures they have taken in many other cases in the past. “What’s different now is that we feel like warriors without weapons, because we are not sure about who is ill, because gloves are not enough, because we may wear the same mask for a week”, says 32-year-old Elpida M, who works in a private nursing home. Her own battle started with a fictitious two-week sick leave, to ensure that all necessary disinfection works were carried out, that consumables were procured and that she wasn’t ill herself. “I could not rely on a system that I knew was not working. It is a matter of personal responsibility, too. If I was to fight, I had to be certain that I was healthy and the there was a safety net in place for me to work”. To date, the nursing home has only had one coronavirus case, which was admitted to a COVID-19 reference hospital.

Women on the front-line face difficult decisions when it comes to their personal life too. Maria Papakosta, a general practitioner at the Health Centre of Spata, took her six-year-old daughter to her parents, as her husband works too, to make sure that, if she gets infected with the virus, she will not transmit it to her daughter and she will be able to continue working. Evangelia Karamichali, head of the nursing sector at the General Hospital of West Attica “Agia Varvara”, where covid cases that do not require Intensive Care Unit hospitalisation are admitted, paints a similar picture. “Fear dominates. A colleague’s partner asked her to sleep at the hospital, while in another case a couple rented a second house to ensure that the virus was not transferred to their home”.

Everyday heroes

I returned home and was short of breath. I had become “corona-phobic”. I would leave my shoes outside and I had bags with me for my clothes, which I washed separately.

The lockdown brought another female-dominated category of employees to the limelight: supermarket cashiers. Previously considered dispensable, they are now increasingly recognised as the “everyday heroes” of the crisis. Katerina K. works under a part-time employment contract for a big food chain. She works fervently in difficult conditions. She describes customers as edgy, bad-tempered, fighting with each other. She works without protective equipment. She only applies disinfectant regularly on her hands. In the first days, the pressure was immense. “I returned home and was short of breath. I had become “corona-phobic”. I would leave my shoes outside and I had bags with me for my clothes, which I washed separately”. Despite the difficulties she considers herself lucky. “As the HR department told us, we shouldn’t nag because in this new crisis we will have a job. Well, this is true, but I won’t lie to you: sometimes I’m thinking that the 800 Euro I would get if I worked in any affected sector would be more than what I get now and I’d be home and safe.”

An equally “heroic” fall was in store for thousands of women working as housekeepers, mainly foreign, who as a rule work illegally without the insurance coupon required by law. Eleni Vaina, owner of recruitment agency PLUS+, describes how the demand for housekeepers plunged on the day the lockdown was announced, adding that this was directly followed by dismissals without compensation, while payments to women working part-time stopped.

In its announcement of 25 March 2020, the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) expressed its concern that one-fourth of working women in the European Union – persons employed in uncertain jobs, such as flight attendants, travel agents, sales assistants, hotel cleaners, hairdressers and similar professions – are likely to face hardship in the coming days and months in paying even for their basic needs, such as staple foods, rent and bills.

Gender-based policies

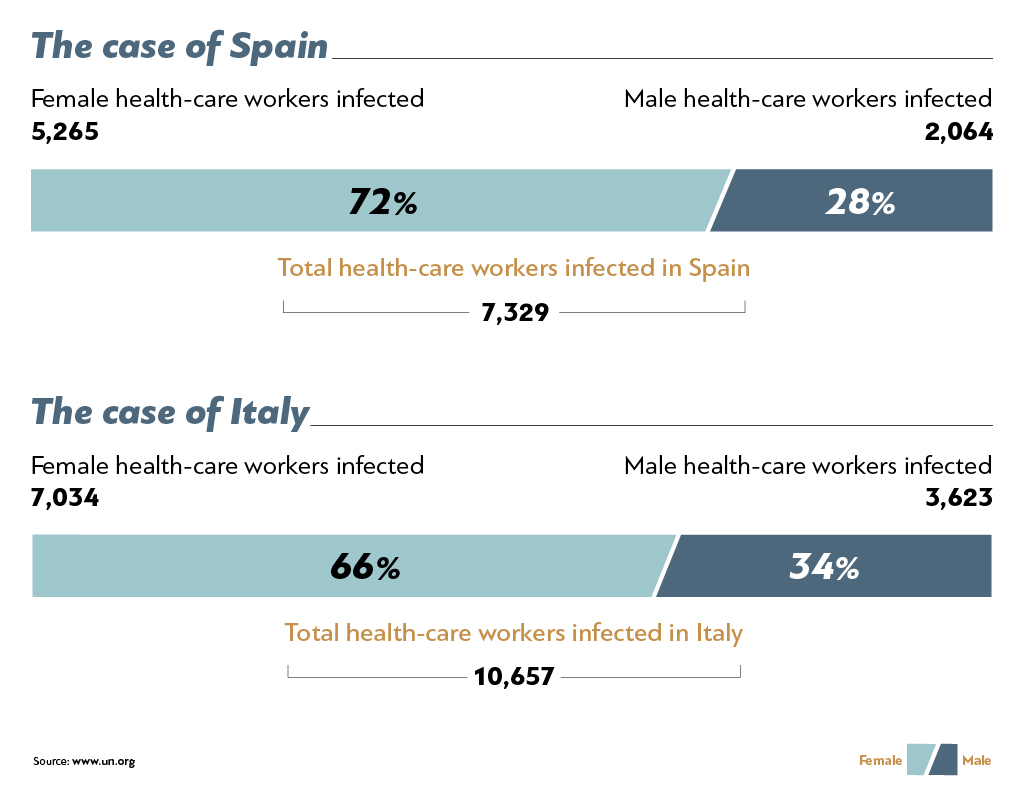

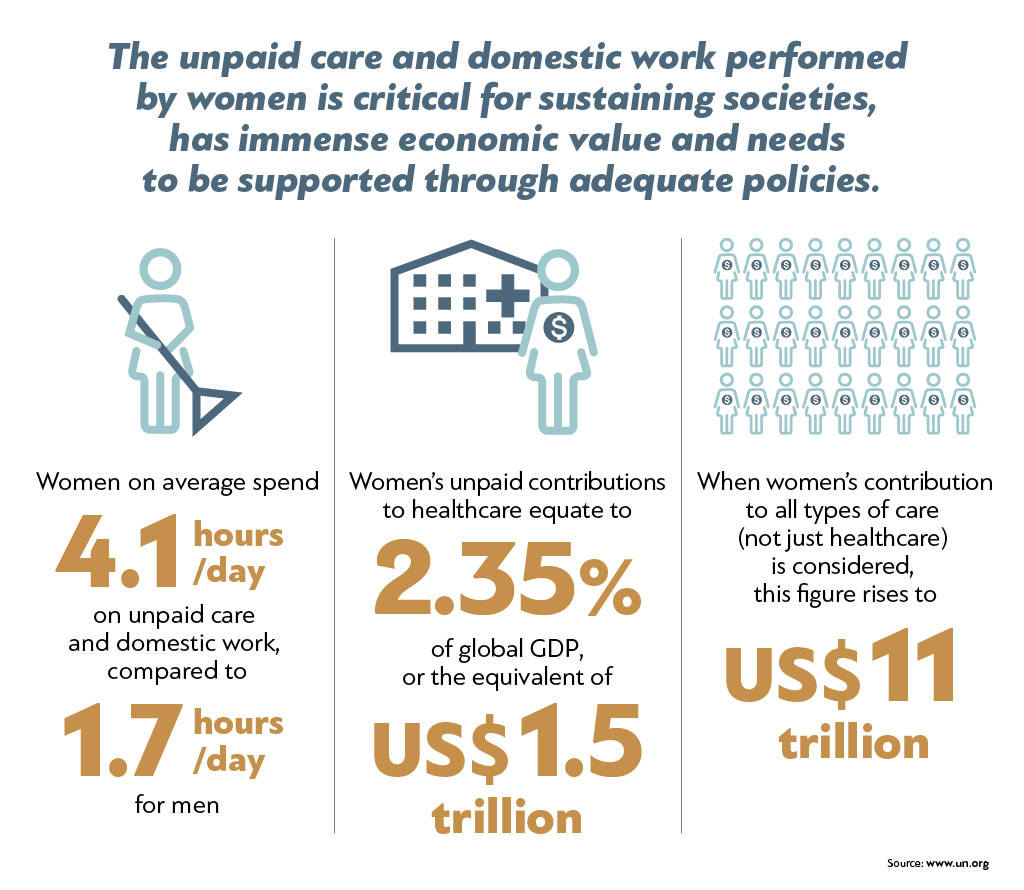

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the role and value of the unpaid, invisible labour carried out by women, whose volume has multiplied and remains high, due to – among else – the short-term isolation of the elderly at home, given that to a large extent they support women’s ability to work.

At best, all these consequences, as recorded in women’s testimonies, are temporary and that, as soon as we return to normality, everything will be as it used to. However, International Organisations and international scientific articles on the consequences of the pandemic do not share the same optimism for the future. The UN Secretary-General’s report of 9 April 2020 states that, although the first indications show that the new SARS-Cov-2 coronavirus is deadlier for men (mainly due to heavier alcohol and cigarette consumption*), its impact will be much harsher for women and girls, just because of their gender in all sectors, from health and economy, to security and social protection.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the role and value of the unpaid, invisible labour carried out by women, whose volume has multiplied and remains high, due to – among else – the short-term isolation of the elderly at home, given that to a large extent they support women’s ability to work. The everyday life of families, communities and the formal economy depend on this invisible labour. Therefore, new policies need to recognise, reduce and redistribute this workload. Otherwise, any steps taken towards gender equality and, mainly, towards the participation of women in labour, will be hindered.

However, in terms of production too, women around the world earn less money, save less, have less stable jobs and work without insurance more often. In this unprecedented crisis, whose features are unlike any other in the past and still under study, the first indications suggest that women’s ability to absorb the financial shock is smaller.

There are no miracle solutions to protect women’s conquests over the last few decades. Nevertheless, in the financial measures and social policies designed now for the post-COVID-19 crisis era, gender must be taken into account. In affected sectors where women comprise the main workforce, there should be greater access to supporting programmes, while the informal economy, which includes thousands of women, should be taken into account.

When I asked her to comment on the matter, the Secretary General for Family Policy and Gender Equality, Maria Syreggela, said that the financial and social policies implemented in Greece are horizontal so far. The easing out of restrictive measures and the consequent restart of the economy will allow a clearer outlook on the overall social and financial situation, for gender-related actions and policies.

*The Lancet (2019), COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak, Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30526-2/fulltext#%20

*To ensure personal data protection, some names of the women who participated with their testimonies are fictional.

—————————————————————————————

Drawing © Dimitris Tsoumplekas, “Simple Life”, 2005, from the Pictionary collection

Infographics Evgenios Kalofolias Infographics source: www.un.org